This post introduces how to understand t-SNE.

Introduction

t-SNE an dimension reduction algorithm, which projects high-dimensional data into low-dimensional space. Thus the algorithm can be used to visualize the data distribution.

To understand how t-SNE works, we first review the SNE algorithms, then we introduce the t-SNE algorithm.

SNE

Method

Stochastic Neighbor Embedding, or SNE, is the previous version of t-SNE.

The basic idea behind SNE is that: data points that are close in high-dimensional space should be close in lower-dimensional space too.

Formally speaking, given a data set $X\in\mathbb{R}^{D\times N}$ consisting of $N$ data points, with each data point lies in $D$ dimensional space. Our goal is to reduce the data points into $d« D$ dimensional space $Y\in\mathbb{R}^{d\times N}$, that is, we seek to find a map $f:\mathbb{R}^{D\times N}\to \mathbb{R}^{d\times N}$ such that $f(X)=Y$. Usually, $d=2$ or $d=3$ for visualization use.

SNE measures “close” in a probabilistic way. The similarity is represented by converting Euclidean distance between data points to condition probabilities:

$$ p_{j\mid i} = \frac{\exp\left(-\Vert\bm{x}_i-\bm{x}_j\Vert^2/(2\sigma_i^2)\right)}{\sum_{k\neq i}\exp\left(-\Vert\bm{x}_i-\bm{x}_k\Vert^2/(2\sigma_i^2)\right)} $$the above equation can be interpreted as the probability of point $\bm{x}_j$ being a neighbor of point $\bm{i}$ is proportional to the distance between them. $\sigma_i$ is the variance of the Gaussian distribution that is centered on data point $\bm{x}_i$. We introduce the method for determining $\sigma_i$ later.

Similarly, we can construct a probability distribution $q$ based on $Y$.

$$ q_{j\mid i} = \frac{\exp\left(-\Vert\bm{x}_i-\bm{x}_j\Vert^2\right)}{\sum_{k\neq i}\exp\left(-\Vert\bm{x}_i-\bm{x}_k\Vert^2\right)} $$where we set the variance as $1/\sqrt{2}$ following the original paper.

$p_{i\mid i}$ and $q_{i\mid i}$ are set $0$ since we are only interested in modeling pairwise similarities.

Now we want $q_{j\mid i}$ are as close as $p_{j\mid i}$, that is, we want two distributions are as close as to each other. This can be measured by Kullback- Leibler divergence, which is written as:

$$ C(P, Q) = \sum_{i=1}^N\mathrm{KL}(P_i\Vert Q_i)=\sum_{i=1}^N\sum_{j=1}^N p_{j\mid i}\log \frac{p_{i\mid j}}{q_{i\mid j}} $$where $P_i=[p_{1\mid i},\dots,p_{N\mid i}]\in\mathbb{R}^N$ and $Q_i=[q_{1\mid i},\dots,q_{N\mid i}]\in\mathbb{R}^N$.

Choosing $\sigma$

Now we introduce how to choose $\sigma$. Note that $\sigma$ determines the distribution of data points, larger $\sigma$ indicates sparser distribution of data points. The original paper uses perplexity to measure such sparsity. It is defined as

$$ \mathrm{Perp}(P_i) = 2^{H(P_i)} $$where $H(P_i)$ is the Shannon entropy of $P_i$ measured in bits:

$$ H(P_i) = -\sum_{i=1}^N p_{j\mid i}\log p_{j\mid i} $$The perplexity can be interpreted as a smooth measure of the effective number of neighbors. The performance of SNE is fairly robust to changes in the perplexity, and typical values are between 5 and 50.

Notice that $p_{j\mid i}$, by setting different value on $\mathrm{Perp}(P_i)$, we can obtain different $\sigma_i$ via binary search.

Optimization

Our goal now becomes minimizing $C(p, q)$ over variables $\bm{y}_1,\dots,\bm{y}_N\in\mathbb{R}^d$, given $p$ and hyperparameter $\sigma_i, i=1,\dots,N$. This can be done via gradient descent methods. The gradient is now given by

$$ \frac{d C}{d\bm{y}_i}=2\sum_{j=1}^N\left(p_{j\mid i} - q_{j\mid i} + p_{i\mid j}- q_{i\mid j} \right)(\bm{y}_i-\bm{y}_j)\in\mathbb{R}^d, \ i=1,\dots,N $$We can write it in matrix form and add a momentum term:

$$ Y^{t+1} = Y^t + \beta\frac{dC}{dY} + \alpha_t\left(Y^{t-1}-Y^{t-2}\right) $$where $\beta$ is the step size and $\alpha_t$ is momentum parameter,

$$ Y^t = [\bm{y}_1^t,\dots, \bm{y}_N^t]\in\mathbb{R}^{d\times N} ,\ \frac{dC}{dY} = \left[\frac{d C}{d\bm{y}_1},\dots,\frac{d C}{d\bm{y}_N}\right]\in\mathbb{R}^{d\times N} $$t-SNE

Symmetric SNE

The first difference between t-SNE and SNE is the probability, t-SNE uses symmetric version of SNE to simplify computations.

Different from SNE, symmetric SNE uses a joint probability instead of a condition probability:

$$ C(P, Q) = \sum_{i=1}^N\mathrm{KL}(P\Vert Q)=\sum_{i=1}^N\sum_{j=1}^N p_{ij}\log \frac{p_{ij}}{q_{ij}} $$where $p_{ij}$ and $q_{ij}$ are defined as

$$ p_{ij} = \frac{\exp\left(-\Vert\bm{x}_i-\bm{x}_j\Vert^2/(2\sigma^2)\right)}{\sum_{k\neq r}\exp\left(-\Vert\bm{x}_r-\bm{x}_k\Vert^2/(2\sigma^2)\right)},q_{ij} = \frac{\exp\left(-\Vert\bm{x}_i-\bm{x}_j\Vert^2\right)}{\sum_{k\neq r}\exp\left(-\Vert\bm{x}_r-\bm{x}_k\Vert^2\right)} $$the problem if joint probability $p_{ij}$ is that if there is an outlier $\bm{x}i$, then $p{ij}$ will be extremely small for all $j$. This problem can be solved by defining $p_{ij}$ from the conditional probability $p_{i\mid j}$ and $p_{j\mid i}$

$$ p_{ij} = \frac{p_{j\mid i}+p_{i\mid j}}{2N} $$This ensures that

$$ \sum_{j=1}^N p_{ij} > \frac{1}{2N} $$for all $\bm{x}_i$, in result, each data point makes a significant contribution to the cost function.

In this case, the gradient of the cost function is now given by

$$ \frac{d C}{d\bm{y}_i}=4\sum_{j=1}^N\left(p_{ij} - q_{ij}\right)(\bm{y}_i-\bm{y}_j)\in\mathbb{R}^d, \ i=1,\dots,N $$t-SNE

Experiments show that symmetric SNE seems to produce maps that are just as good as asymmetric SNE, and sometimes even a little better.

However, there is a problem with SNE, that is, the crowding problem, which manifests as a tendency for points in the low-dimensional space to be clustered too closely together, particularly in high-density regions of the data.

The causes of the crowding problems are:

- Data points in high dimensional space tend to far from each other, which makes the distance information less useful.

- SNE aims to preserve the local structure of the data points, but it can struggle with non-linear relationships. The projected data points will be closed to each other due to this reason.

- The optimization algorithm used by SNE can get stuck in local minimum.

To alleviate the crowding problem, t-SNE is introduced in the following way: In the high-dimensional space, we convert distances into probabilities using a Gaussian distribution. In the low-dimensional map, we can use a probability distribution that has much heavier tails than a Gaussian to convert distances into probabilities. This allows a moderate distance in the high-dimensional space to be faithfully modeled by a much larger distance in the map and, as a result, it eliminates the unwanted attractive forces between map points that represent moderately dissimilar data points.

t-SNE uses student t-distribution in low-dimensional map:

$$ q_{ij} = \frac{\left(1+\Vert\bm{y}_i-\bm{y}_j\Vert^2\right)^{-1}}{\sum_{k\neq r}\left(1+\Vert\bm{y}_i-\bm{y}_j\Vert^2\right)^{-1}} $$A Student t-distribution with a single degree of freedom is used, because it has the particularly nice property that $\left(1+\Vert\bm{y}_i-\bm{y}_j\Vert^2\right)^{-1}$ approaches an inverse square law for large pairwise distances $\Vert\bm{y}_i-\bm{y}_j\Vert$ in the low-dimensional map.

Compared to Gaussian distribution, t-distribution is heavily tailed。

A computationally convenient property of t-SNE is that it is much faster to evaluate the density of a point under a Student t-distribution than under a Gaussian because it does not involve an exponential, even though the Student t-distribution is equivalent to an infinite mixture of Gaussians with different variances.

The gradient of t-SNE is given by

$$ \frac{d C}{d\bm{y}_i}=4\sum_{j=1}^N\left(p_{ij} - q_{ij}\right)(\bm{y}_i-\bm{y}_j)\left(1+\Vert\bm{y}_i-\bm{y}_j\Vert^2\right)^{-1}\in\mathbb{R}^d, \ i=1,\dots,N $$The advantages of t-SNE gradients over SNE are given by:

- The t-SNE gradient strongly repels dissimilar data points that are modeled by a small pairwise distance in the low-dimensional representation.

- Second, although t-SNE introduces strong repulsions between dissimilar data points that are modeled by small pairwise distances, these repulsions do not go to infinity.

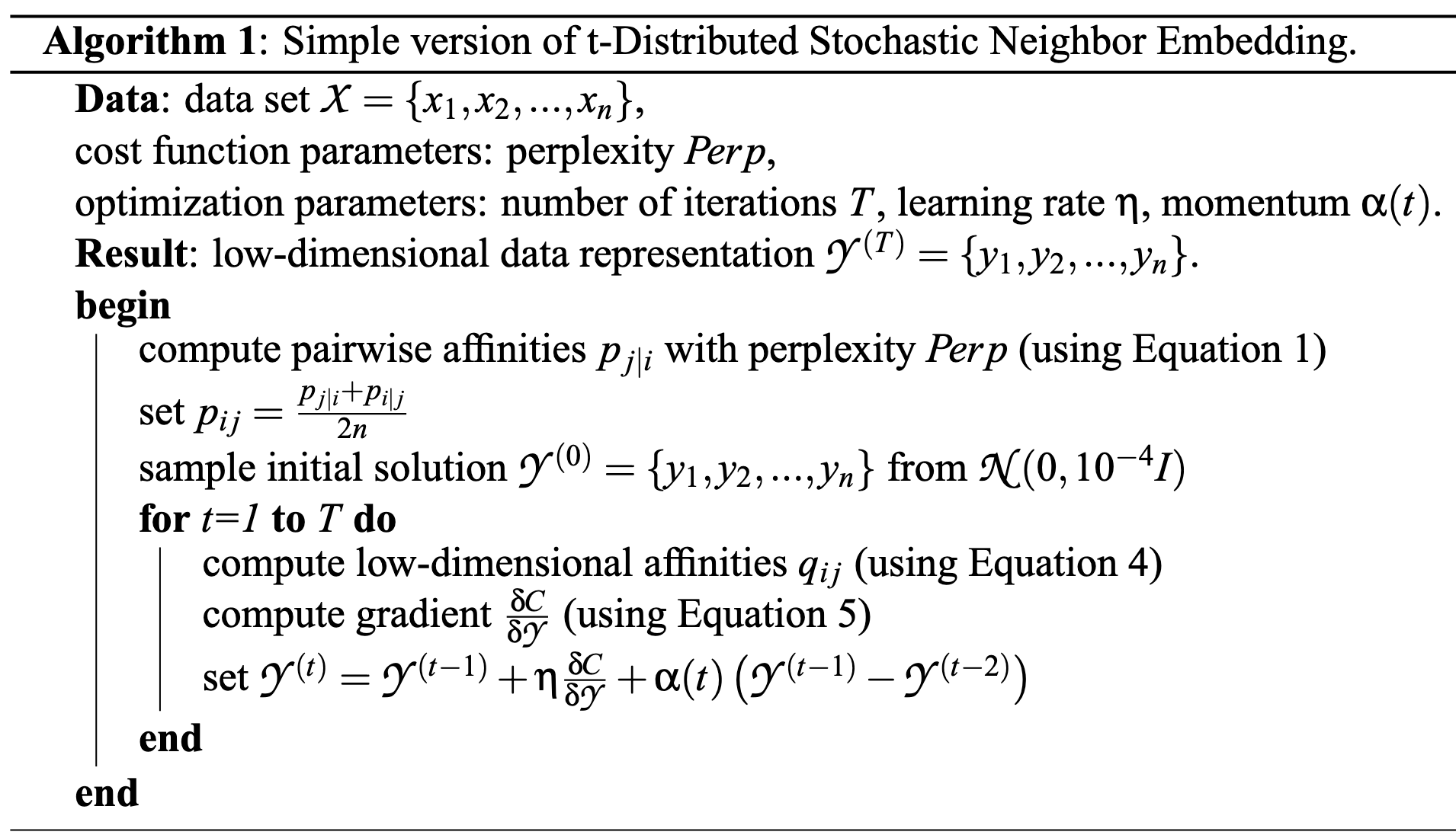

The algorithm is given as follows:

Optimization

There are some optimizations that can be used to improve performance of t-SNE:

- Early compression, which is used to force the map points to stay close together at the start of the optimization

- Early exaggeration, which is used to multiply all of the pi j’s by, for example, 4, in the initial stages of the optimization